Diversions: A Memoir by David Balton

I had never seen Jane jump up and down with excitement before. Not when I proposed to her. Not on our wedding day – she had not gotten enough sleep the night before to do any jumping whatsoever. And not even when, after more than a year of failed attempts, we learned that she was pregnant for the first time.

What caused Jane to explode in a paroxysm of joy was an email from Will Shortz, The New York Times puzzle editor:

Hi Dave and Jane,

First, the good news in short ... your Bill Bryson Acrostic is scheduled for the Times on Sunday, June 18.

The bigger good news: Out of all the Acrostics I’ve gotten since Emily and Henry retired, yours is by far my favorite.

The quote is interesting. The word list is lively and varied. The clues are smart, cultured, and on-target - not vague as crossword clues sometimes are, but nailing the meanings of the answers. In addition, nine of your clues/answers relate to the subject of the quote (Rome or Italy). Obviously, that bit of elegance is unnecessary and can’t be done every time, but it’s very much appreciated here.

In sum, absolutely lovely. I would welcome more Acrostics from you.

Let’s see how far this goes.

Thanks for everything.

Will

When I was a kid, we did not have a subscription to The New York Times. Instead, Mom ventured out every Sunday to the local shop that sold the paper and returned with the precious Sunday crossword puzzle. Then the debate began as to who got first crack at it. Things often got out of hand. For a time, we made Mom stop at the library on the way home to xerox the magazine section's puzzle page. But the quality of copy wasn't great, and the paper would smudge if you tried to erase anything. We wound up fighting over who got to do the original version.

I mostly left games and puzzles behind during my time in college and law school. That said, one moment from those years provided some sort of inspiration, or perhaps a favorable omen. Becky Stone, one of my college friends, introduced me to her father shortly after The New Yorks Times ran a crossword puzzle that he had constructed. He described in delighted detail his experience riding a commuter train into New York the day his puzzle appeared.

"Everyone around me seemed to be working on my puzzle at the same time — including the guy in the seat right next to me. It was all I could do not to poke him in the arm and say, "Hey, how about that clue for 37 Down!"

I thought then … maybe someday.

I returned to a life of games and puzzles after meeting Jane, who had also grown up in a family that partook of these diversions. She and I played Scrabble on some early dates; I like to say that Jane fell for me because I was the first guy who could beat her at Scrabble, at least occasionally. I learned from her that games like Scrabble could be the subject of wagers — the loser might, for example, be obliged to wash the dinner dishes. One memorable game result required Jane to play the Harvard football fight songs on her violin for me. They never sounded so good. Later in life, the stakes occasionally involved changing one of the kids' diapers, an approach never mentioned by Dr. Spock in his guidance on baby care.

Jane also taught me how to play blackjack, something she later claimed to regret. Twice I tagged along when the National Symphony Orchestra traveled to San Juan, Puerto Rico, to take part in the Pablo Casals Festival. The orchestra housed us in upscale beach resort hotels — the Condado Plaza one year, El Caribe Hilton the other. Both had casinos. One evening, Jane led me into one of those casinos and suggested we take a seat at a low-stakes blackjack table.

The basic elements of the game proved easy enough to assimilate — so easy, in fact, that I returned to the casino on my own the next evening while Jane was off at a concert. I won $60, due entirely to my wizardry at cards and owing nothing to beginner's luck. Blackjack has been a part of my life ever since — usually about once a year, often in exotic locations such as Monte Carlo, Moscow, Nice, or Rhodes. I taught my sister Ruth to play; in Reno she promptly won $200 and just as promptly retired from the game.

As Jane and I approached our first wedding anniversary, I surprised her with an acrostic puzzle I made by hand, based on a poem by our multi-talented 6-inch lion, Ponce de Leon:

Year One is both history and herstory

Your fun has just started

Before I could give Jane that puzzle, she insisted that I open the anniversary card she had gotten for me. Imagine my amazement on finding inside … a hand-made acrostic by Jane (her first), based on a quotation from Dorothy Sayers’ Busman’s Honeymoon:

which in these days may be considered a record.

But then you see, Padre, we are old-fashioned country-bred people.

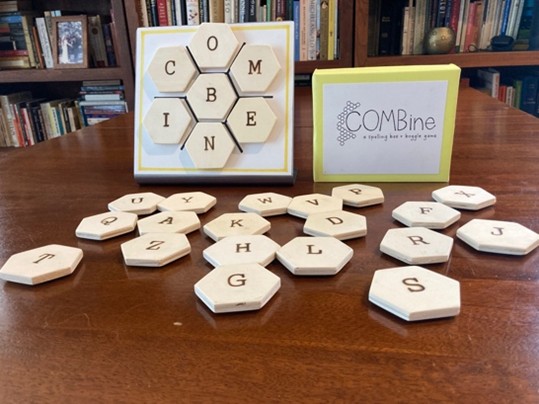

Our kids, Becca and Timmy – surprise, surprise – grew up in a world full of games and puzzles. Card games, board games, made-up games – you name it. Timmy took to chess even before he was potty-trained; indeed, to spur the process along, we promised to play chess with him only if he would sit on the toilet while we played. Christmastime often involved the making and exchanging of homemade games, such as Animopoly (made by the kids for Jane), our own version of Authors (made by the parents for Becca) and, much later, a game that Becca invented, built, and punningly named Combine, which blends Boggle and the Spelling Bee.

As parents, we viewed game-playing as a natural and enriching part of our fun family life. We generally dismissed comments received from visiting friends and neighbors concerning the hypercompetitive zeal that our charming family put on full display while engaged in a game. Once, in high dudgeon over a dispute Scattergories, Becca placed a call to an out-of-town friend seeking support for her position. It occurred to me that, had people from Child Protective Services ever paid us a visit during one of our marathon gamefests, they might have brought into question our fitness as parents. I could imagine them asking, “Shouldn’t your children be in bed by now?” or “Do you ever have actual conversations?”

Admittedly, there is a fine line between a healthy passion for games and puzzles and worrisome addictions. Although we managed to keep Becca and Timmy away from the high-tech computer games that swallowed up the time of many other kids, particularly boys, Timmy lost a lot of sleep to lower-tech offerings, such as Tetris and Backyard Baseball.

Timmy’s interest in chess really blossomed in elementary school, thanks to “Mr. G,” as everyone called him. After-school chess club sessions and Saturday morning tournaments at the U.S. Chess Center in downtown D.C. became regular features of Timmy’s young life. His passion for chess endured as Timmy became Tim. He picked up the game again as an adult and, in 2025, spent a week of vacation time participating in an international chess tournament in Reykjavik.

For Becca, Jane and me, the day cannot truly begin until we complete The New York Times crossword puzzle and a few other puzzle offerings, particularly the Spelling Bee. Becca has taken to doing the daily crossword when it becomes available online the night before. Jane still does her puzzles on paper, usually in pen, using as her source a NYT Puzzle-A-Day Calendar that Tim provides as a Christmas gift every year. And as of this writing, Jane and I are on pace to play 120 games of Upwords this year, a marked decrease from last year’s total.

A list of all the other games regularly played over the years in our house – and on trips – might raise some eyebrows. To name just a few: Scrabble, Scrabble Crossword Cubes, Boggle, Monopoly, Apples to Apples, Settlers of Catan, Codenames, dominoes, backgammon, canasta, Taboo, Chameleon, cribbage, poker, Uno, Risk, Chronology, Mille Bornes, Iota ... the list goes on.

All this is normal and even … admirable, right?

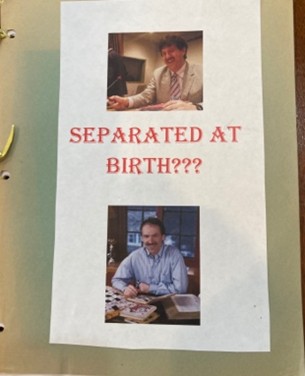

Like many people, I regard the puzzles that appear in The New York Times as the gold standard and Will Shortz as a sort of folk hero. Knowing this, a few years back Jane cobbled together as a present for me a whimsical booklet entitled “Separated at Birth” – about Will and me and the things we share, beginning with moustaches.

Jane and I loved the 2005 documentary Wordplay, featuring Will in his role as puzzlemeister and a broad range of crossword enthusiasts, including Bill Clinton, Jon Stewart (“Pens? I fill out my crosswords in Gluestick!”), Mike Mussina, Ken Burns, and the Indigo Girls. About half the film takes place in Stamford, Connecticut, home of the wacky and wonderful American Crossword Puzzle Tournament, where hundreds of nerdy, pencil-wielding Mensa types gather each year to revel in their collective quirkiness and compete at puzzle-solving.

Inspired by Wordplay, I sent my first crossword to Will Shortz in 2006, a 15x15 puzzle that I hoped would be selected for one of the Monday-Saturday editions of The Times. It wasn’t. I unsuccessfully submitted a few more crosswords, including a 21x21 attempt with a musical theme that I felt sure was on par with those that appear each Sunday in The New York Times Magazine. In sending it to Will, I mentioned in a cover letter that I constructed the puzzle in part while in Antarctica, thinking that might add to its allure. It didn’t.

That’s when I turned my attention in earnest to making acrostic puzzles. I found some software that significantly sped up the construction process by doing much of the grunt work automatically – drawing the grid, numbering the boxes and the corresponding dashes, and keeping track of the letters. In 2008, I started a tradition of making acrostics for other family members to solve at Christmastime, targeted to their interests and laden with inside-the-family jokes.

I also submitted an acrostic to Will Shortz, who, as gently as possible, responded with information I should have realized long before: since the late 1990s, every biweekly acrostic in The New York Times had been constructed by Emily Cox and Henry Rathvon. They had cornered this particular market, and for good reason. Their acrostics were gems – witty, erudite, tricky, and just plain fun.

Time passed; I put my dream of publishing a puzzle in The Times on the back burner. I also ditched my old PC and Dell laptop for a fancy MacBook Air, only to discover that my acrostic-making software didn’t work on it. After failing to find new software for my Mac, I wrote to Will for advice, who put me in touch with Emily and Henry. They kindly connected me with Mike Shenk, a puzzle maven and constructor who also designed their Mac-compatible acrostics software. I am still astonished that Mike provided that same software to me – someone he didn’t know from Adam – and refused any compensation.

Mike’s software allowed me to start producing acrostics again. I also found myself with two new correspondents – Emily and Henry, who turned out to have things in common with Jane and me beyond a love for puzzles. Henry had an aunt in the Foreign Service and a sister, Larry, who taught Spanish to both Becca and Timmy at Georgetown Day School. Henry was also a devotee of classical music.

Before long, Jane was offering Henry recommendations on classical artists and recordings. And, with some trepidation, I sent Emily and Henry – or HEX, as they are known in puzzledom – a couple of my acrostics. They could not have been more encouraging and helpful in their comments.

Then came the moment in 2023 when Emily and Henry gave us a heads-up that they were stepping down as the constructors of acrostics for The Times. I saw a window of opportunity.

“Jane, let’s make some acrostics and send them to Will Shortz,” I suggested.

“You, mean, make them together?”

“Exactly. We can find some quotes together, I can make the answer lists and you can write the clues. What do you think?”

“I think you’re crazy. You’re working at the White House. I’m up to my eyeballs playing with the orchestra and my chamber groups. Where will we find the time for this? Plus, Will probably has dozens of people lined up already.”

“Details, details.”

Over the next couple of weeks, Jane and I made three acrostics, including one based on a hilarious quote I remembered from Bill Bryson’s travel memoir Neither Here nor There:

Turn any street corner in Rome and it looks as if you’ve just missed a parking competition for blind people. … Romans park their cars the way I would park if I had just spilled a beaker of hydrochloric acid on my lap.

We spiced up that puzzle with clues and answers relating to Rome and to driving: Bernini, the Spanish Steps, the Trevi Fountain, La Dolce Vita, the Ides of March, I Claudius, Etruscans, Empire Falls, the autostrada, and Honda. We packaged up the three acrostics, sent them off to Will, and crossed our fingers.

Four days later came his response:

I’m interested in using the Bryson acrostic, if you can format the manuscript the way Emily and Henry usually do (which greatly saves me time in laying out the page). It’s a nice quote and a solid word list.

That sounded like a done deal to me. Jane was not so sanguine. Just because Will was interested in using one of our puzzles didn’t mean he would actually do so. But she worked with me to reformat and resubmit the puzzle. Some weeks later came Will’s further response confirming that our acrostic would run on June 18 and characterizing our puzzle as “absolutely lovely,” sending Jane jumping around our living room.

June 18, 2023, turned out to be Father’s Day. That weekend, the Washington Nationals were hosting the Miami Marlins, for whom Andy Pugh’s son, also named Tim, worked crunching baseball statistics. Because Tim Pugh was coming to town for the series, the sizeable Pugh clan organized a family gathering in DC. Andy and his wife, Kristen, came in from Pittsburgh and stayed at our place.

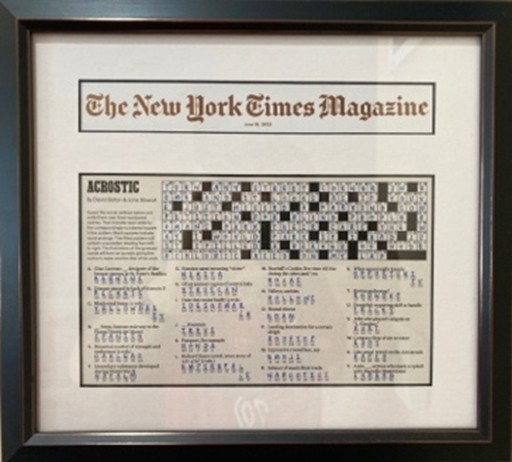

On that Sunday morning, Jane – like my mom so many years earlier – went to the local store to purchase a copy of The New York Times. But this edition contained something never before seen in that paper: a byline by David Balton and Jane Stewart.

We somehow managed to contain our excitement and kept this news a surprise for Andy and Kristen until after the paper made its way into our home. And then, after a traditional Father’s Day breakfast in bed that included Andy – ta da! We opened the magazine section to one of the back pages. There, in black and white, appeared our first published acrostic.

Andy and Kristen were duly astounded. In explaining how this blessed event had come to pass, I began with the story of Becky Stone’s father, the guy who watched a train car full of people working on his crossword puzzle more than forty years earlier. After breakfast, and unbeknownst to us, Andy snuck away with the magazine section to a local Kinkos and made some twenty copies of our newly minted acrostic for his relatives to work on in between innings of the Nats-Marlins game, to which we were also invited. And that’s how I got to experience my own version of that train car moment.

Emily Cox and Henry Rathvon produced well over 600 acrostics for The New York Times in a storied run that ended in 2023. We certainly have no ambitions to match that unbelievable record. But as of June 2025, we have published fifty-two acrostics of our own and feel a bit less like impostors with each passing month.

Our acrostics appear every other week in two places: in the hard copy edition of The New York Times Magazine and on www.xwordinfo.com, a website run by our friend and collaborator Jim Horne. We have also created a blog at www.nytacrostics.com. Every two weeks, we post some thoughts about the current acrostic and seek feedback from solvers, a process that has been both gratifying and instructive.

Becca, who also constructs acrostics, serves as our beta tester. She solves each puzzle and provides brilliant and detailed feedback, including such gems as “You two obviously have no idea how dating sites work” and “Dad, that’s not a thing!” For display purposes, Becca also deployed her remarkable handwriting in filling out our first NYT acrostic, which appears proudly framed above our old-fashioned dictionary stand:

On December 8, 2024, The Washington Post ran an article profiling a Manhattanite named Hilda Jaffe, who was 102 years old at the time. The piece, which described Ms. Jaffe as “sharp as a tack,” followed her through her daily routine and hinted at the secrets to her longevity and mental acuity. One of Jane’s colleagues called to our attention an arresting photograph included in the article.

Ms. Jaffe is working on one of our NYT acrostics … and doing so in pen. Zowie!

In 2025, Jane and I decided to attend the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament, which members of the puzzleverse simply call the ACPT. When we told Will of our decision, he promptly asked if we would appear as featured speakers during the Friday evening events that precede the crossword-solving competitions on Saturday and Sunday. Will also asked us to construct a special acrostic to be solved on Friday evening.

Although we each had considerable experience with public speaking, the ACPT presented a new kind of challenge. How could we connect to this unusual audience? What could we say to them that was truly original? What if most of them wished that Emily and Henry were still making the acrostics for The New York Times?

We needn’t have worried. The large group who turned out for the 2025 ACPT – roughly 1,000 in all – were exceptionally friendly and welcoming. In speaking to the crowd on Friday evening, we asked how many of them regularly did the acrostics in The Times. Quite a lot of them raised their hands. And after we spoke – about how we came to make acrostics, about our challenges and joys in constructing them, about our “day jobs” – the audience embarked on a competition to solve the acrostic we had made for the occasion, an especially difficult offering based once again on a quote from Bill Bryson:

English speaker[s] confronted with agglomerations of letters like tchst, sthm, and tchph would naturally conclude that they were … unpronounceable. Yet we use them every day in … matchstick, asthma, and catchphrase.

Tom Nawrocki needed only 11 minutes and 30 seconds to complete the acrostic, something we wouldn’t have thought humanly possible. The ACPT winner Paolo Pasco took only a minute more, with Dan Schwartz just one more minute behind. We realized then that we were in the presence of geniuses of a special sort.

And, of course, we got to experience a second “train car” moment, this time on a grand scale, watching enthralled as that ballroom full of people worked on a puzzle of our creation.